U.Mars — Encyclopedia

U.Mars — Encyclopedia

Basic Astronomy and the Nighttime Sky

Energy comes in many forms and can transform from one type to another. Charged particles — such as electrons and protons — create electromagnetic fields when they move, and these fields transport the type of energy we call electromagnetic radiation, or light.

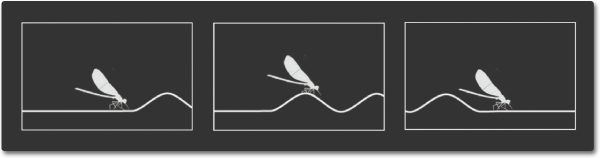

Mechanical waves and electromagnetic waves are two important ways that energy is transported in the world around us. Waves in water and sound waves in air are two examples of mechanical waves. Mechanical waves are caused by a disturbance or vibration in matter, whether solid, gas, liquid, or plasma. Matter that waves are traveling through is called a medium. Water waves are formed by vibrations in a liquid and sound waves are formed by vibrations in a gas (air). Classical waves transfer energy without transporting matter through the medium. Waves in a pond do not carry the water molecules from place to place; rather the wave's energy travels through the water, leaving the water molecules in place, much like a bug bobbing on top of ripples in water.

Mechanical waves and electromagnetic waves are two important ways that energy is transported in the world around us. Waves in water and sound waves in air are two examples of mechanical waves. Mechanical waves are caused by a disturbance or vibration in matter, whether solid, gas, liquid, or plasma. Matter that waves are traveling through is called a medium. Water waves are formed by vibrations in a liquid and sound waves are formed by vibrations in a gas (air). Classical waves transfer energy without transporting matter through the medium. Waves in a pond do not carry the water molecules from place to place; rather the wave's energy travels through the water, leaving the water molecules in place, much like a bug bobbing on top of ripples in water.

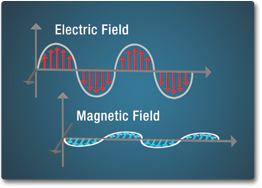

Electricity can be static, like the energy that can make your hair stand on end. Magnetism can also be static, as it is in a refrigerator magnet. A changing magnetic field will induce a changing electric field and vice-versa — the two are linked. These changing fields form electromagnetic waves. Electromagnetic waves differ from mechanical waves in that they do not require a medium to propagate. This means that electromagnetic waves can travel not only through air and solid materials, but also through the vacuum of space.

In the 1860's and 1870's, a Scottish scientist named James Clerk Maxwell developed a scientific theory to explain electromagnetic waves. He noticed that electrical fields and magnetic fields can couple together to form electromagnetic waves. He summarized this relationship between electricity and magnetism into what are now referred to as "Maxwell's Equations."

In the 1860's and 1870's, a Scottish scientist named James Clerk Maxwell developed a scientific theory to explain electromagnetic waves. He noticed that electrical fields and magnetic fields can couple together to form electromagnetic waves. He summarized this relationship between electricity and magnetism into what are now referred to as "Maxwell's Equations."

Heinrich Hertz, a German physicist, applied Maxwell's theories to the production and reception of radio waves. The unit of frequency of a radio wave -- one cycle per second -- is named the hertz, in honor of Heinrich Hertz. His experiments with radio waves both demonstrated that the velocity of radio waves was equal to the velocity of light (that radio waves were a form of light), and determined how to make the electric and magnetic fields detach themselves from wires and go free as Maxwell's waves — electromagnetic waves.

Electromagnetic waves are formed by the vibrations of electric and magnetic fields. These fields are perpendicular to one another in the direction the wave is traveling. Once formed, this energy travels at the speed of light until further interaction with matter.

Light is made of discrete packets of energy called photons. Photons carry momentum, have no mass, and travel at the speed of light. All light has both particle-like and wave-like properties. How an instrument is designed to sense the light influences which of these properties are observed. An instrument that diffracts light into a spectrum for analysis is an example of observing the wave-like property of light. The particle-like nature of light is observed by detectors used in digital cameras — individual photons liberate electrons that are used for the detection and storage of the image data.

Light is made of discrete packets of energy called photons. Photons carry momentum, have no mass, and travel at the speed of light. All light has both particle-like and wave-like properties. How an instrument is designed to sense the light influences which of these properties are observed. An instrument that diffracts light into a spectrum for analysis is an example of observing the wave-like property of light. The particle-like nature of light is observed by detectors used in digital cameras — individual photons liberate electrons that are used for the detection and storage of the image data.

One of the physical properties of light is that it can be polarized. Polarization is a measurement of the electromagnetic field's alignment. In the figure above, the electric field (in red) is vertically polarized. Think of a throwing a Frisbee at a picket fence. In one orientation it will pass through, in another it will be rejected. This is similar to how sunglasses are able to eliminate glare by absorbing the polarized portion of the light.

The terms light, electromagnetic waves, and radiation all refer to the same physical phenomenon: electromagnetic energy. This energy can be described by frequency, wavelength, or energy. All three are related mathematically such that if you know one, you can calculate the other two. Radio and microwaves are usually described in terms of frequency (Hertz), infrared and visible light in terms of wavelength (meters), and x-rays and gamma rays in terms of energy (electron volts). This is a scientific convention that allows the convenient use of units that have numbers that are neither too large nor too small.

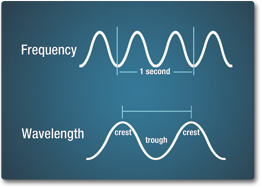

The number of crests that pass a given point within one second is described as the frequency of the wave. One wave — or cycle — per second is called a Hertz (Hz), after Heinrich Hertz who established the existence of radio waves. A wave with two cycles that pass a point in one second has a frequency of 2 Hz.

The number of crests that pass a given point within one second is described as the frequency of the wave. One wave — or cycle — per second is called a Hertz (Hz), after Heinrich Hertz who established the existence of radio waves. A wave with two cycles that pass a point in one second has a frequency of 2 Hz.

Electromagnetic waves have crests and troughs similar to those of ocean waves. The distance between crests is the wavelength. The shortest wavelengths are just fractions of the size of an atom, while the longest wavelengths scientists currently study can be larger than the diameter of our planet!

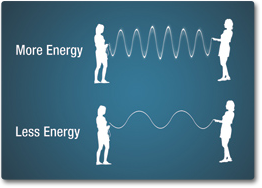

An electromagnetic wave can also be described in terms of its energy — in units of measure called electron volts (eV). An electron volt is the amount of kinetic energy needed to move an electron through one volt potential. Moving along the spectrum from long to short wavelengths, energy increases as the wavelength shortens. Consider a jump rope with its ends being pulled up and down. More energy is needed to make the rope have more waves.

An electromagnetic wave can also be described in terms of its energy — in units of measure called electron volts (eV). An electron volt is the amount of kinetic energy needed to move an electron through one volt potential. Moving along the spectrum from long to short wavelengths, energy increases as the wavelength shortens. Consider a jump rope with its ends being pulled up and down. More energy is needed to make the rope have more waves.

See also:

Thanks to:

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Science Mission Directorate. (2010). Anatomy of an Electromagnetic Wave. Retrieved January 12, 2014, from Mission:Science website: https://science.nasa.gov/ems/02_anatomy