U.Mars

— Encyclopedia

U.Mars

— Encyclopedia

Basic Astronomy and the Nighttime Sky

Telescopes collect light from distant objects and focus it to form a clear

image you can see easily. The size of the telescope's primary optics (mirrors or lenses) determine how

much light the telescope can gather at once; a large telescope can gather more light than a smaller

one, enabling you to see objects that might otherwise be too faint.

The size of the primary

lens (in a refracting telescope; see Types) or primary mirror (reflecting telescope)

determines its Light-Gathering Power

(LGP). The more light can be gathered and focused, the fainter the objects that become detectable.

Since the light-gathering power of a circular telescope's mirror is related to

the mirror's area (where a circle's area = pi * R2), an example mirror "A" of twice the diameter of

another mirror "B" has four times the light-gathering power of that mirror "B." If you compare the

light-gathering power of a major research telescope, with a primary mirror 10 m across, to a modest

personal telescope with a primary mirror of diameter 20 cm, then it becomes more like a factor of a

few thousand in the difference!

Think also, for a moment, of how many times larger even that modest backyard

telescope's lens or mirror is than the pupils of your eyes, and you may quickly appreciate just how

much more light gathering power you gain by using any telescope to view faint objects, over just

looking with your unaided eyes.

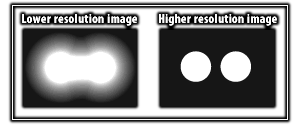

A telescope's spatial resolution is also related to the

span of its optics (lenses or mirrors). A larger baseline (effective diameter) increases spatial

resolution, the ability to see detail in objects; this larger baseline can be achieved by both larger

single primary mirrors and by using multiple mirrors together (even if they are spaced apart; see

section on Interferometers in Types).

A telescope's spatial resolution is also related to the

span of its optics (lenses or mirrors). A larger baseline (effective diameter) increases spatial

resolution, the ability to see detail in objects; this larger baseline can be achieved by both larger

single primary mirrors and by using multiple mirrors together (even if they are spaced apart; see

section on Interferometers in Types).

Magnification is

often thought of as an important property of telescopes, but actually it does not increase

light-gathering power. Magnifying an image, or "zooming in," does not make the image brighter, but

only reduces the portion of the sky on which you're focusing; at higher magnification, what light

you've gathered is spread back out over a larger area. Higher magnification can cause a small, bright,

point light to blow up into a dimmer disk, sometimes useful for noting contrasts in surface detail of

such objects in planets. Small telescopes (meant for eyes, instead of CCDs) often have a wide

selection of eyepieces of differing magnifications, some useful for looking at planets or nebulae, and

others useful for stars and clusters, etc. Overall,

magnification is one of the least-important properties of modern telescopes (being especially

irrelevant to telescopes feeding light gathered to electronic detectors).

Other parts of telescopes include devices (like manual knobs or dials) to help

fine-tune the focus the light from the primary mirror to the eyepiece, sturdy mounts to keep the

telescope steady and avoid shaking images seen through the telescope, and often motors to help the

telescope keep tracking a particular target object by moving slowly to compensate for the Earth's

rotation (so that the target object does not slide out of view).

See also:

Thanks to:

Space Telescope Science Institute. (2005). Telescopes from the Ground Up. Retrieved January 12, 2014, from:

http://amazing-space.stsci.edu/resources/explorations/groundup/